Behold Jesus of Bennington

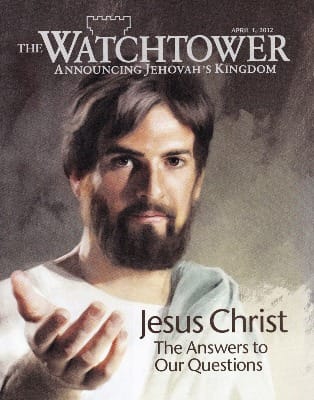

They were very nice, this pair of African American ladies, well dressed and courteous and on my porch late in the morning. They were Jehovah’s Witnesses and at my door to invite me to a “Memorial of Jesus’ Death” at a conference center a dozen miles from my house. We chatted a bit, and I accepted a flyer and thanked them and wished them a good day. They smiled and thanked me for my time and walked to my next-door neighbor’s.

The Jesus portrayed on the flyer had a Greek nose, a good haircut, a full beard, and a mustache trimmed precisely along his upper lip. His curly hair and beard were brown as were his eyes, but his facial features and skin tone were not of a sun-baked Semite. This was a white man. And a damned handsome one, at that. Jewish? Not so much. More what we used to call Black Irish.

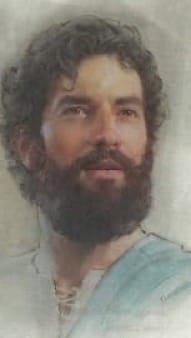

Scholarly consensus casts Jesus as a Judean from Galilee. We must assume that he looked like most Judean men, because the Bible is mute on the matter. This would mean brown or black hair trimmed relatively short, a beard, olive-brown skin, and brown eyes. (And short not just of hair but in stature by our standards—probably about 5’ 5”, average for the time.) Most likely lean of build.

For centuries Christianity has been uniquely intent on ostensibly realistic portraits of its central figures. Muslims regard pictorial representations of Mohammed or Allah as blasphemous. Images of the Buddha tend toward abstract iconography. Hindu gods often have more arms than typically found in humans. The Bible concentrates on what Jesus said, not how he looked, and with no contemporaneous descriptions or images Christian writers and painters have had to invent the face of their savior, with interesting variability. A number of early Christian texts from the first centuries C.E. describe Jesus as ugly, sometimes deformed by a hunched back. Why? To establish him as an outsider or outcast? The 2nd-century apocrypha known as Acts of John describes him as small and bald. By the 4th century, he had undergone a makeover. Jerome of Sidon and Augustine of Hippo surmised he must have been beautiful, "beautiful as a child, beautiful on earth, beautiful in heaven.”

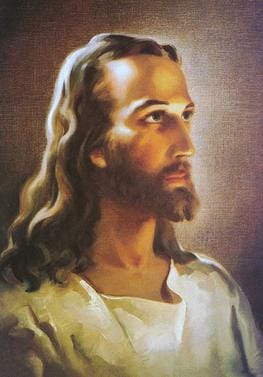

The 20th-century Chicago commercial artist Warner E. Sallman aligned himself with Jerome and Augustine. In 1940, he took a sketch he’d done and rendered it in oils as “Head of Christ” in response to a request from a professor at the Moody Bible Institute for a “manly” representation. (Don’t want no sissy saviors.) Sallman had no inkling that his portrait would go on to be one of the most reproduced images in American history. A member of the Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant of America, now the Evangelical Covenant Church, Sallman portrayed the savior as a lot more Scandinavian than Judean, with blue eyes and the flowing locks of a shampoo advert, locks that, in the highlights at least, look more blond than brown.

In their book Color of Christ, Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey estimate that by the 1990s Sallman’s portrait had been reproduced a half-billion times. I don’t know—I doubt anyone knows—why Jesus of the Flowing Locks became the dominant visual trope. Widespread distribution of Sallman’s picture—thousands and thousands were printed on cards and sent to American GIs in the Second World War, for example—must have been a factor, but similar images already abounded in the 19th century. Publications by Jehovah’s Witnesses, like The Watchtower, seem to favor Black Irish Jesus. But however he wears his hair, the Jesus in these pictures is always white. You really have to squint to see him as a Jew. Nah, not even then. Viewed from any angle, he looks more like an artisanal candlemaker in Vermont circa 1976. Not Jesus of Nazareth but Jesus of Bennington.

What did the nice black ladies who knocked on my door make of the image on the flyer? Perhaps when they looked at it they didn’t see race; they saw the face of their savior radiating wisdom, love, holiness, a face that happens to have pale skin that signifies nothing. No less than Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, in 1957, “The color of Jesus’ skin is of little or no consequence,” “a biological quality which has nothing to do with the intrinsic value of the personality.” Jesus “would have been no more significant if His skin had been black. He is no less significant because His skin is white.” My meagre understanding of contemporary Christianity involves an emphasis on a personal god and a personal savior, on an emotional relationship with Christ that I think would be alien to other faiths. In that context, I can understand how the artists who made paintings and frescoes and church windows might be inclined to portray a Jesus who looks more like his worshippers. A more realistic figure of a tough, weathered, brooding Jew with callused hands and maybe haunted eyes is a tougher sell as your warm personal savior. In person, I suspect Jesus was less a comfort and more of a challenge, but that might just be me. He did have a way of calling out bad thinking and bad behavior. Remember the moneylenders.

But following that reasoning, shouldn’t there be images of a black Jesus in African American churches? Of a brown Jesus in Latino churches? Perhaps there are; it’s not like I can call on direct experience. But I’m guessing not. And what about Christian churches in Asia or sub-Saharan Africa? Oy.

We do not do so well at grounding ourselves in reality. We choose reassurance over attention to detail, over attention to the actual hard-edged and messy and ambiguous world. Maybe we have to. I think turning Jesus into a visual cliché, a banal generic bro with great hair, does him and his teachings an injustice. And I surprise myself with how strongly I feel about that, given that I subscribe to no faith. Life is good, but it’s never simple. Mysteries abound.

Member discussion