Iron gall ink and the sister Shakespeare never had

Letter No. 73: Includes bit rot, bit flip, parasitic wasps, Pliny the Elder, and more use of “lattice” than usual.

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf proposed a thought experiment: “Let me imagine, since facts are so hard to come by, what would have happened had Shakespeare had a wonderfully gifted sister, called Judith, let us say.”

She was as adventurous, as imaginative, as agog to see the world as he was. But she was not sent to school. She had no chance of learning grammar and logic, let alone of reading Horace and Virgil. She picked up a book now and then, one of her brother’s perhaps, and read a few pages. But then her parents came in and told her to mend the stockings or mind the stew and not moon about with books and papers. They would have spoken sharply but kindly, for they were substantial people who knew the conditions of life for a woman and loved their daughter—indeed, more likely than not she was the apple of her father's eye. Perhaps she scribbled some pages up in an apple loft on the sly, but was careful to hide them or set fire to them.

Woolf’s scenario does not end well for her Judith Shakespeare. But about 80 years later, there was a happy literary outcome. Author Rachel Kadish read A Room of One’s Own, and Woolf’s angry musing prompted her to ponder a character—an intelligent, questioning, determined girl with a facility for language and a drive to make sentences who lived in a culture that almost seemed designed to thwart her every ambition. Who would she be, when would she live, where would her story unspool? As this character began to coalesce, Kadish, at the time a writer-in-residence at Stanford University, availed herself of some Stanford history classes. There she learned of the 16th-century Portuguese Jewish diaspora, when Jews fled the Iberian Inquisition and established an important Jewish community in Amsterdam. From there, Jews began resettling London around 1630. Now Kadish had a milieu for her character, who became Ester Velasquez, the protagonist of her fine novel The Weight of Ink.

Novels can grow from curious prompts. William Faulkner said The Sound and the Fury began with an image of a little girl with muddy underwear climbing a tree. One day E.L. Doctorow realized he had a picture in his mind of men wearing tuxedos on a boat in the middle of a harbor in the middle of the night. What were they doing on the water at that hour? Why were they dressed in tuxedoes? Something about the scene compelled him to start writing, and the men became gangsters, one of them had his feet in a tub of hardening cement, and the story grew into the excellent novel Billy Bathgate. Another wonderful Doctorow book began with the author at his desk lost for what to write next. He looked around the room, thought about the house in which he lived at the time, and for want of anything better scribbled, “In 1902 Father built a house at the crest of the Broadview Avenue hill in New Rochelle, New York.” Which became the first sentence of the wonderful Ragtime, the novel that brought Doctorow international acclaim plus a boatload of money.

Rachel Kadish has a copious mind in service to profound curiosity and the compulsive thoroughness of a dedicated scholar. She also possessed the rare ability to synthesize Virginia Woolf’s imaginative premise, her own experience as a Jewish woman, and the myriad things she learned about life in London in 1650.

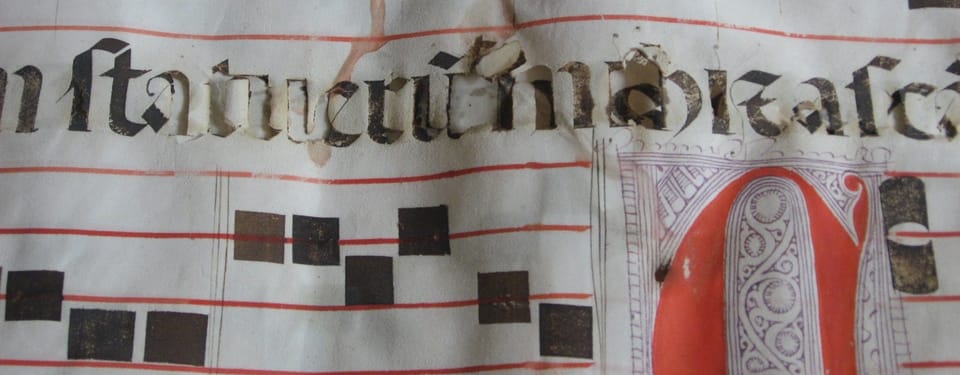

I learned how people did their laundry. I visited London; consulted with experts in 17th-century Jewish history and in Judeo-Portuguese and Ladino dialects; learned how to write with a quill pen. I visited conservation laboratories, where I fell in love with the texture of 17th-century paper and the quirks of 17th-century ink–specifically, ion gall ink. Certain forms of iron gall ink dissolve paper fiber over centuries, so that the letters and words eventually burn their way through the page on which they’re written. The results of iron gall ink damage can be hauntingly beautiful: sheets of 17th-century paper like lattices, with holes in the shape of the words an unknown hand once inked onto the page.

Ah, iron gall ink. Gaius Plinius Secundus—if you’ve heard of him it’s as Pliny the Elder—was a 1st-century Roman natural philosopher, military commander, and writer who in his spare time befriended the emperor Vespasian, which surely was a good move. He died in 79 CE from the brave, noble, but ultimately bad move of trying to rescue a friend from the massive eruption of Mt. Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii.

Pliny wrote a lot, including a lost history of Rome’s Germanic wars that was reputed to encompass 20 volumes. He left scribbled accounts of his many observations of nature and of his experiments, like the one where he took a piece of papyrus, soaked it in tannin, then dripped an iron salt solution on it. Why did he do that? Who knows. But he noted that upon contact, the iron salt instantly turned the tannin-bathed papyrus black.

A parasitic wasp designated Cynips quercusfolii lays eggs in the tenderest limbs of oak trees. When the larvae hatch they begin eating the tree, goddam little ingrates. As they snack the larvae secrete an irritant that causes the tree to produce a spherical growth around the parasite—a gall, also known as an oak apple, which is a much better name that never caught on. In time people all over the world discovered that they could crush these galls before the eggs hatched and ferment them in water to produce gallotanic acid, better known as tannin, essential for turning hides into leather.

Then, because people just can’t stop messing around, they discovered that if they dropped crystals of iron sulfate in a solution of tannin and water (or wine), they got a blue-black liquid—the chemical reaction Pliny had discovered, now in a bottle. Christian Europe may have learned this from Arabs, who used the solution as fabric dye and as mascara. The Romans called this liquid atramentum, and distinguished three types; only one concerns us here: atramentum librarium, which the Romans used as ink. Iron gall ink.

By the way, the ancient Greeks knew of a similar substance, but had a much better name for it. They called it chacantum, which means “blood of copper.”

By 2500 BCE scribes had learned to make ink from lampblack in a liquid suspension. It was a deep saturated black, which was nice, but it was also smudgy and not waterproof. Iron gall ink? That was indelible. Writers working on anything meant to endure longer than a jotted note or a receipt for delivery of a dozen goats embraced the ink and for centuries, from the Middle Ages to colonial America, its use was ubiquitous. (You can still buy it.) The oldest known manuscript regarded as a form of the Christian Bible, the Codex Sinaiticus, was scribed in the 4th century with iron gall ink.

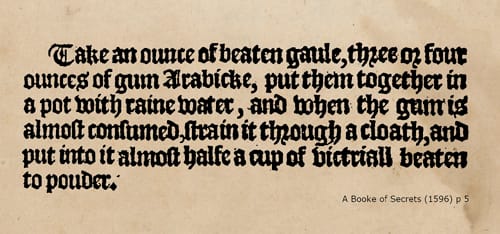

There are iron gall recipes from 5th-century Carthage. A Booke of Secrets from 1596 includes a contorted recipe that begins (with period spelling), “Take halfe a pint of water, a pint wanting a quarter of wine, and as much vineger, which being mixed together make a quart and a quarter of a pint more, then take six ounces of gauls beaten into small pouder and sifted through a sive, put this pouder into a pot by it selfe” and goes on for quite a bit more. The Dutch East India Company took iron gall ink so seriously it issued an authorized formulation. And you did not mess with the Dutch East India Company.

Who knows why, but in 1935 the US government established a standard iron gall ink formula of its own:

- 11.7 g tannic acid;

- 3.8 g gallic acid;

- 15 g iron(II) sulfate;

- 3 cm3 hydrochloric acid (used to prevent sediment forming);

- 1 g carbolic acid;

- 3.5 g china-blue aniline dye (water-soluble);

- 1000 cm3 distilled water.

In the 1980s, art forger Eric Hebborn found that when he couldn’t obtain oak galls, rotten acorns worked. Good to know.

Iron gall ink resists erasure by human hands but carries the potential to erase itself. Over centuries, it can react with air, moisture, and paper to eat the page that it’s written on; one might see justice in ink made at the expense of parasitic wasps eventually parasitizing itself. Just or not, when this happens letterforms become ghosts. Texts become stencils. This is no small matter to conservators who fear that centuries-old documents deep in the neglected corners of the world’s archives may be erasing themselves.

Digital archives have their own version of the iron gall ink problem. It’s called bit rot. Solid-state data drives use electrical charges to store information bits, and those charges can leak away. The bits stored on magnetic media can lose their magnetic orientation and disappear. (There’s a great term sometimes used when discussing bit rot: “silent corruption.”)

There’s a more exotic form of digital degradation. Cosmic radiation strikes everything, everywhere, all the time. It’s shooting through you as you read this. Outside Earth’s magnetic shield, spacecraft are subject to an even greater constant bombardment by cosmic rays. When a ray strikes the data drive of a satellite at just the right place, it can change a 0 to a 1. This is called bit flip, and it may sound improbable but it does happen and can wreak havoc within the computer that controls the spacecraft. Cosmic ray bit flip also has been implicated in the malfunction of heart pacemakers and for autopilots on commercial airliners suddenly doing crazy things with the airplane.

Where was I going with all of this? Right, Rachel Kadish and “…iron gall ink damage can be hauntingly beautiful: sheets of 17th-century paper like lattices, with holes in the shape of the words an unknown hand once inked onto the page.”

That image has stayed with me. The things that prompt the creation of art are multifarious and weird and funny and mysterious and paradoxical and disturbing, not always healthy but maybe holy. Prompted by Kadish, I picture myself in an archive studying a document from, I dunno, 1588. I further picture myself doing something one should never ever do: I pick up the crumbling page and take it outside and hold it in front of my face to gaze at the world through a lattice of vanished words put there by human hands 436 years ago.

It’s a wonderful way to picture what we do all the time. We see life through a scrim of stories from yesterday and last year and stories from Babylon and stories from every age in between. I see my life through a lattice of stories of my father and my mother and stories from my own hands and stories told by Homer and Conrad and Hemingway and McPhee and Didion, and from Heart of Darkness and Hamnet and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and A Boys’ Book of Baseball Stories.

Rachel Kadish, prompted by Virginia Woolf imagining Shakespeare’s sister, and inspired by a Stanford history course to look at 1650s London through pages crumbling under their own weight of iron gall ink, created Ester Valesquez. I think about that sequence and say, How could she have done anything else? Because when I gaze through a scrim of vanished text in my own mind, discerning vague shapes that whisper ghostly words, I am all but helpless, I have to write something, and I’m happy to do so. From ink has come my life. I’ve added my few bits to the lattice of stories. And that feels like a fine life. That feels sufficient.

Coda

Rachel Kadish’s respect for historical accuracy and the earnest pursuit of authenticity led to a bit of comedy. For an important scene in The Weight of Ink, she wanted a dying character to utter a few words from Consolação às Tribulações de Israel, a book revered by the Portuguese Jewish diaspora. Determined to get it exactly right, she went to the Widener Library at Harvard to examine a copy of the actual 1533 book. She could not read Portuguese, so her plan was to take some smartphone pictures of a few pages that looked promising, then send them to a historian who was willing to translate. From this she could decide on a sentence that her character might speak in the original Portuguese. It’s the sort of lunatic scavenger hunt that will be familiar to many obsessive writers.

The historian examined the images, then gently informed Kadish that she’d photographed the table of contents.

Member discussion