The sad and perplexing tale of Morgan Cornwell

Morgan Cornwell was born in 1819 or 1820 in Jefferson County, Kentucky. By the first shots of the American Civil War, he lived in Indiana, where he enlisted in the 24th Indiana Volunteer Infantry. The 24th Indiana fought in some of the major battles of the war, including Shiloh and the several clashes of the Vicksburg Campaign. One of the latter took place at Champion Hill, Mississippi, and here something, probably a bullet, mangled one of Private Cornwell’s arms.

Morgan Cornwell was my second great-grandfather.

Telling you all that I know about him won’t take long. He is listed as 30 years old in the 1850 US federal census, birthplace Kentucky. Jefferson County, which includes Louisville, is inferred as a more specific birthplace because there is record of him marrying there at age 17. His bride was Ann Robinson, who gave birth to two daughters before dying in 1842; a third daughter, Mary, is recorded as born in 1842, suggesting Ann died in childbirth.

On January 28, 1844, Morgan married again, this time in Orange County, Indiana, roughly 50 miles from where he was born. His second wife was Mary Adeline Mayfield, who seems to have been called Polly. Records indicate that their marriage was fruitful, producing four daughters and three sons. Most of Orange County’s early settlers had been Quakers who would not abide slavery in North Carolina and left the South with a number of freed slaves. This might have influenced a crucial decision on the part of Morgan some years later.

Historians designate April 12, 1861 as the first day of the American Civil War, when Confederate forces bombarded Fort Sumter, off Charleston, South Carolina. Though enthusiasm for the war varied across Indiana, which had many farmers who had migrated from the South, by the end of the war in 1865 about 210,000 Hoosiers had served in the Union army and navy. The last recorded combat death of the war was Private John J. Williams. He was from Indiana.

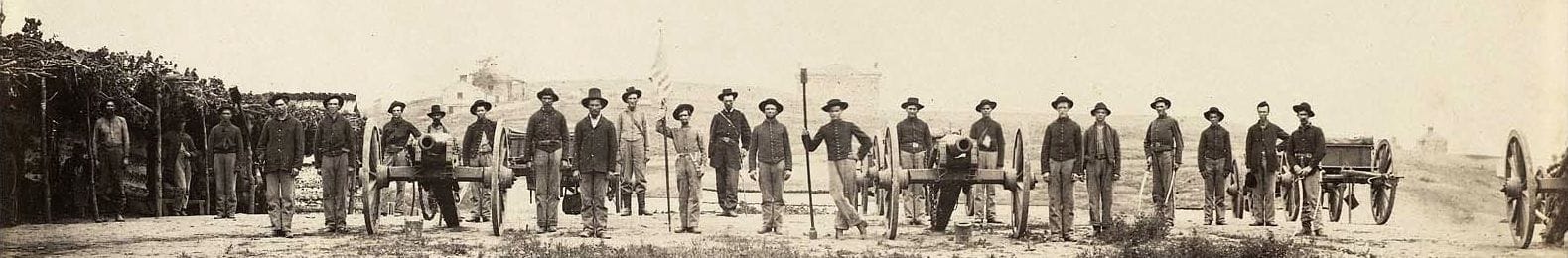

Morgan Cornwell could not have joined the war much faster. He signed up on the 24th Indiana’s muster date, July 31, 1861. Less than a month later, the regiment was in Missouri. By mid-February 1862, it was in Tennessee, and in six weeks it violently collided with the Confederate Army of Mississippi at Shiloh. In A History of the Trials and Hardships of the Twenty-fourth Indiana Volunteer Infantry, Richard J. Fulfer, who served in the regiment, wrote of the fighting on that battle’s second day: “The earth shook as if with an earthquake. It seemed as if nothing could live in the hell of fire. One could taste the sulfur, and the shell and bullets could have been stirred with a stick. The atmosphere was blue with lead.” In two days, the Union army suffered 13,047 casualties. Thirty-two were from the 24th Indiana.

After Shiloh, the regiment marched south into Mississippi to join the struggle to seize Vicksburg and control of the Mississippi River. One of the campaign’s battles took place at Champion Hill, where 32,000 Union soldiers slammed into 22,000 Confederates. Again, Pvt. Fulfer:

Regiment after regiment poured death and destruction into our ranks until we had only a little squad left, to rally around At the first volley the most of our little battalion dead and wounded. I dropped into a ditch and loaded and fired three shots at the rebels. They were so close that I could see the whites of their eyes.

It seemed as though the hill was filled with rebels. On they came and I had to get up and change my position. When about halfway up the hill, I ran into a squad fighting hand to hand. Here was the place where the old 24th almost lost its flag, and also, Colonel Barter almost lost his hand. The colors were shot out of it and the flag staff was split into three pieces. Corporal Steel carried the flag off of the field.

We could not get reinforcements and the chance of any of us being saved was a forlorn hope, but just at the last moment, we were saved by reinforcements.

… No person except those who were pickets on that field, that dark night, can imagine the horrors of that awful bloody field of death and destruction. The groans of hundreds of wounded and dying could be heard on the still night air, and one could imagine that they saw them in their mangled condition, begging for water and calling on God for help.

On this battlefield, Morgan Cornwell’s luck ran out. He suffered a catastrophic wound to one of his arms, probably from a .58 caliber hollow Minié bullet that would have flattened on impact, causing massive damage sufficient to require amputation in a Union army field hospital. As everyone knows, this was a dreadful procedure performed without anesthetic by a “doctor” who indiscriminately wielded a hacksaw because he didn’t know what else to do. But what everyone knows is wrong. According to the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, 95 percent of Union army surgery patients were anesthetized, usually by chloroform. A trained surgeon most likely cut away soft tissue with care to create flaps of skin, sawed through the bone quickly to minimize bleeding, filed smooth any jagged edges of bone, tied off the arteries with thread, then sutured the skin flaps over the stump, with an opening to let the wound drain. An experienced field surgeon could complete an amputation in 10 minutes, which was vital for minimizing loss of blood. At the time, it was by far the superior way to treat serious battle wounds. By the best estimates I could find, about 70 percent of soldiers survived the surgical procedure.

Amputations saved lives. Infection took them. Medicine did not yet understand the importance of antiseptic procedures. Saws were not sterilized and surgeons did not wash their hands. By the time the 24th Indiana mustered out in 1865, it had registered 88 soldiers killed or mortally wounded in battle. The toll from disease and accident was 204. My ancestor survived his wound and amputation. He made it back home to Indiana, probably by rail and wagon, since the North did not yet control the Mississippi River. The journey might have taken weeks. In pain and likely traumatized, Morgan Cornwell nevertheless made it to Indiana by July 1, 1863, according to historical records.

Three weeks later, he was dead. I’ve not found an official cause of death, but I suspect what, during the war, was known as “hospital gangrene.”

I know that I am supposed to be proud of my second great-grandfather. He fought for his country and gave his life in the righteous cause of preserving the Union and defeating the traitorous Confederacy and its chattel slave economy. He answered the call as a patriotic American. But for me, it is not that simple. More often than not, I regard patriotism with the same wariness and skepticism that I apply to nationalism. And I will never understand why men so willingly go to war.

When Morgan Cornwell enlisted, no one, least of all him, had any idea if the Confederate States of America posed an existential threat to the rest of the United States. He had no idea if the war would come to Indiana, threatening the safety of the people he loved. There is no record of his being an abolitionist. Yet, he went into battle as fast he could. Did he respond to the rallying cries of politicians and influential people in town, as well as friends and neighbors, everyone caught up in war fever? Maybe. But at age 41, he should have known better. Estimating the average age of a Union foot soldier is an imprecise enterprise, but the available numbers seem to cluster around 25 years; of all enlistees, about 70 percent were 23 or younger if you trust the estimates. So Morgan Cornwell lined up with men, and no doubt some boys, who were half his age, to fight an enemy he had little knowledge of, an enemy that had done nothing to him, an enemy that, at the time, had no discernible interest in conquering his country or threatening his loved ones. When Mr. Cornwell, blacksmith, became Private Cornwell, soldier, the war was not a fight for survival; it was an abstract cause, and nothing has the potential for a cynical waste of human lives like a cause.

I doubt any of that was on his mind. But how could his family not be? This was a man with a wife and, depending on how many had survived, as many as 10 children. Had he stayed home, followed events as best an illiterate man (as noted in the federal census) in a backwater could, and by late 1862, or 1863 had he become fearful that the war might be lost and with it all he valued and loved, his volunteering to fight would be more comprehensible to me. But to leave a wife and all those children at a time when hardly anyone knew what was really happening, or what might happen?

I’m probably underestimating the intense pressure to join the throng that was enlisting for the Union, and how signing up for the army was preferable to making oneself an outsider, perhaps ostracized or labeled a coward. Maybe he’d spent so many years among Quakers, he’d absorbed their horror of slavery. Maybe he felt a compulsion he couldn’t begin to articulate. I will never know. But it’s his decision, more than his death, that haunts me.

Member discussion