Could you speak a bit more slowly?

Or, no one writes Tironian shorthand anymore.

Cicero, 1st century BCE Roman orator, skeptic, writer, lawyer, and statesman talked his way onto the wrong side of Mark Antony in 43 BCE, which was a bad idea. Antony proscribed him, which sounds mild in Latinate English; translated into forthright Anglo-Saxon , Mark Antony put Cicero on a death list. When assassins tracked him down, Cicero, according to Seneca the Elder, uttered these last words: “I go no further: approach, veteran soldier, and, if you can at least do so much properly, sever this neck.”

Dr Essai does not believe that for a moment, but acknowledges its quality as invented dialogue and a sly bit of snark. Whoever made it up deserves a dram of the good stuff.

Before his neck’s severance, Cicero earned a reputation as Rome’s finest orator. (The Chalcedonian Christians later declared him a “virtuous pagan,” which the doctor considers an honorific well worth pursuing.) He wrote a great deal, especially letters, but much of what we have in his name was written down by other people, speeches and legal arguments and other oratory transcribed by secretaries. Foremost among these transcribers was Marcus Tullius Tiro.

Tiro faced the same problem as every secretary, college student, and newspaper reporter ever: how to keep up with the flow of spoken words well enough to produce an accurate and comprehensive account. The mouth works faster than the hand. Plus Tiro wasn’t taking notes with a smooth gel pen on a Rhodia pad. He was writing, sometimes while walking, with a reed pen called a calamus that had to be dipped every so many words and hardly slid along the page without friction.

If scholarly supposition has it right, Cicero recognized the problem and charged Tiro with inventing a form of Latin shorthand. Tiro did so, and then some. He created a system of letters and symbols to stand in for prepositions, words, abbreviations, and phrases. He may have borrowed from a Greek shorthand that had been in use for a century or more. No one can say how many symbols Tiro came up with — presumably he wrote it down, but no such key is known to have survived — but successors began adding to it until, according to Isidore of Seville writing around 630 CE, no less than Seneca himself had topped it up to 5,000 symbols. Five thousand.

Ponder for a moment. That’s a lot of shorthand. Tiro, Seneca et al had to comb Latin, its lexicography, its substantial literature, and its stultifyingly dull legal documents, to find 5,000 words, titles, phrases, and boilerplate sentences that could be replaced by letters and dots and lines and squiggles. They invented a parallel Latin with a massive alphabet — a whole new written language remarkable for its simultaneous concision and precision. And created a whole new level of literacy reserved for those who had memorized and become adept at the system. The irony is this elevated literacy would have existed mostly among slaves. Sweet.

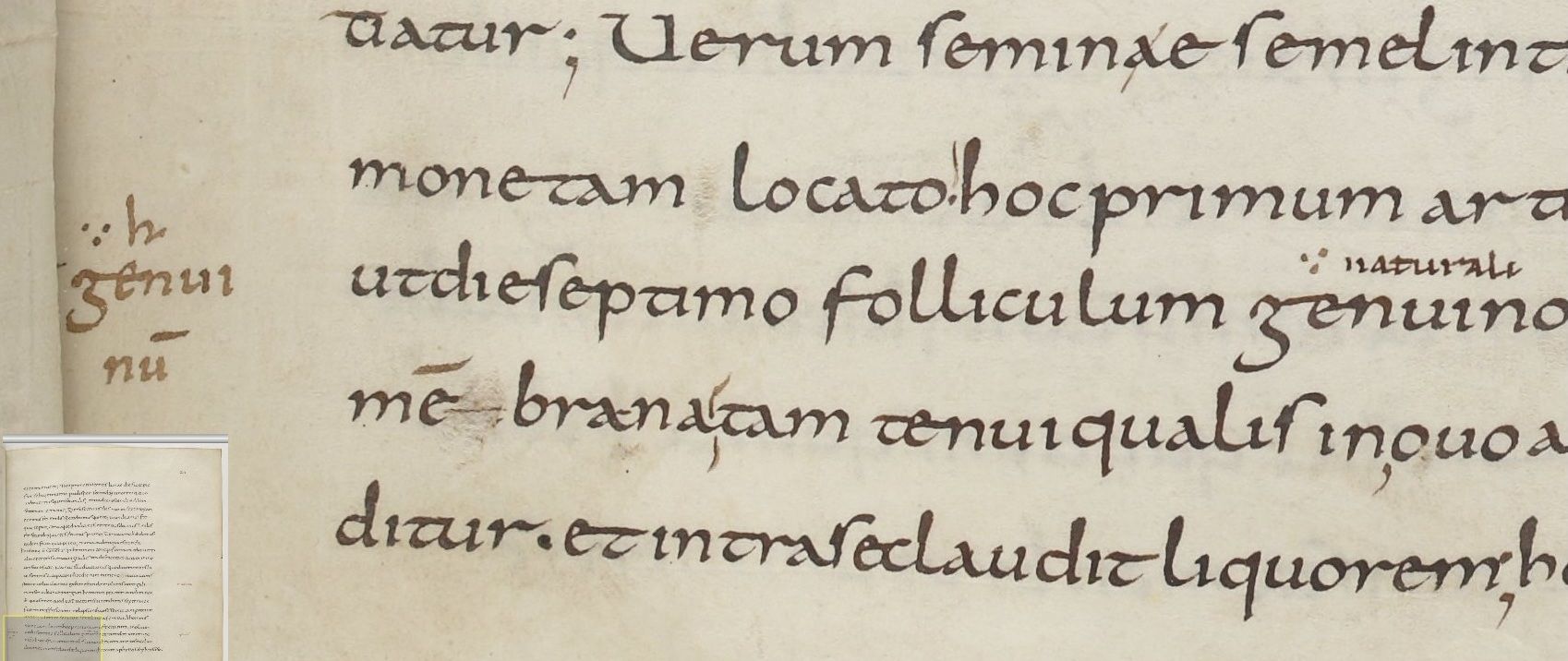

Tironian notation might be a mere curiosity from the time of togas were it not for monastic scribes in the Middle Ages who not only employed it, but expanded it to around 14,000 symbols. (!) Most of the documentation dates from the Carolingian dynasty in the 8th and 9th centuries. Emilia Henderson, writing for the British Library’s medieval manuscripts blog, noted:

The Carolingian interest in shorthand was part and parcel of the revival of learning, art, and book production often known as the Carolingian Renaissance. In the Admonitio generalis (General admonition), an important collection of legislation issued in 789, the most famous Carolingian ruler, Charlemagne, implored that schools be established for the learning of not only the Psalms, chant, and grammar, but also notae, or ‘written signs.’

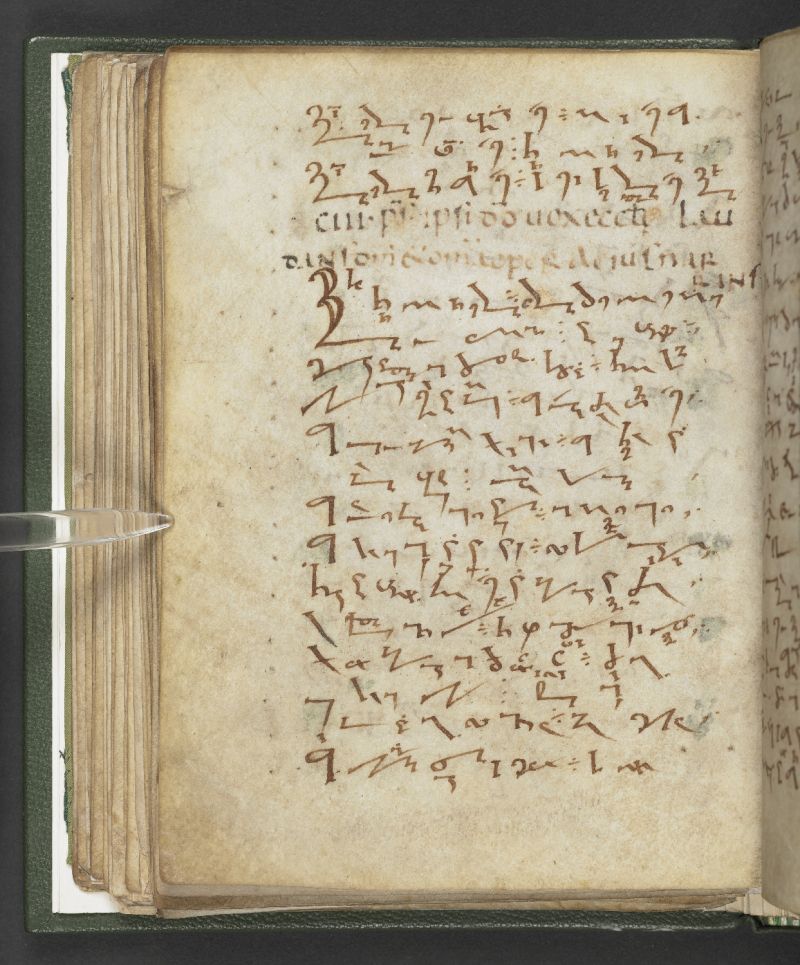

Based on the surviving manuscript evidence, certain Carolingian monastic schools took a particular interest in Tironian notes. The scriptorium at Tours seems to have been one of the earliest centers to master this shorthand system, even including it in its famous illustrated pandect Bibles, such as the Moutier-Grandval Bible. Occasionally an entire book might be written in Tironian notes, such as this late 9th-century copy of the Psalms…

Monasteries stopped using Tironian shorthand for a few centuries (until Thomas Becket brought it back), possibly because it’s resemblance to runes (if you squint hard) may have led to an unfortunate association with witchcraft and magic. In the doctor's mind, lending credence to this story are the Irish, who still use a Tironian symbol — ┐— known as et, for agus, which is Irish for “and.” As we all know, the Irish have always been a witchy people.

Medieval scribes often added unauthorized marginalia to manuscripts, some of it obscene, some of it written in Tironian notation. Dr Essai cheers himself with the thought that these toilers, who worked long hours in austere conditions without union representation and nary a pay-raise in sight, might have used Tiro’s invention to throw a little mud at management. It’s juvenile, but the doctor loves the idea that tucked into a corner of a psalter might have been some shorthand for Brother Cadfael — what a dick.

Member discussion